What is mentoring?

Mentoring is an institutional practice that is usually engineered by the institution that pairs the mentor and the mentee. It could be of several kinds.

- Universities, who have a mission to train students and researchers, use mentoring to support student training

- Academic journals, who have a mission to publish quality content, use peer-review, which is itself a peculiar form of mentoring

- Businesses use mentoring to train new hires

When one thinks of mentoring, often the bilateral relationship between a more senior person and a less senior person (professionally and/or academically) is what comes to mind. However, the meaning of mentoring at GDN is vastly different and aligns with our mission.

What mentoring means at GDN

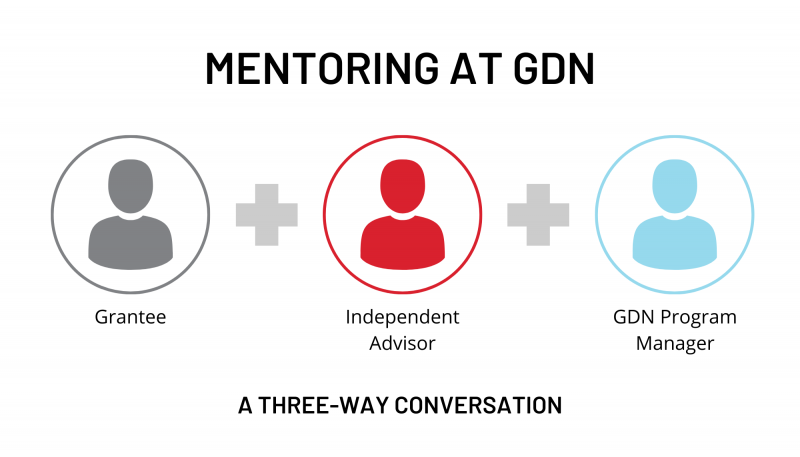

At GDN, we think of mentoring as a pretext for critical discussion around the structure, potential and progress of a project, that involves a relationship and three-way conversation between three parties, the advisor, the grantee, and GDN program managers, each one having a specific role to play in the success of a project.

At GDN, we use mentoring to implement our mission to support the development of local capacity to address development challenges in LMICs through evidence and innovation. It plays a key role in all our grant making, specifically in our research grants, research capacity strengthening grants, and even institutional capacity strengthening grants (more on this below.) Given that GDN works across a wide range of themes and countries and cannot (by definition) guarantee deep in-house expertise on the substance and implementation context for all of our grants, mentoring is vital to our functioning and capacity building mission.

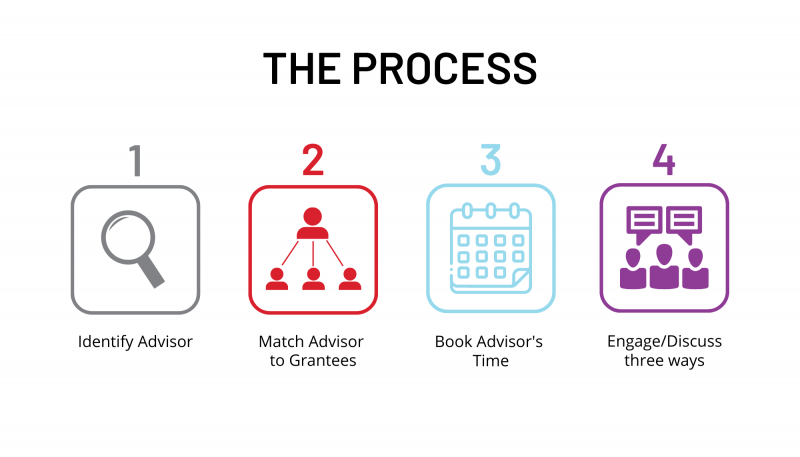

Mentors at GDN are called ‘Scientific and Technical Advisors’ or ‘Technical Advisors’ or henceforth, ‘Independent Advisors’. Our program managers identify and match them with teams working on projects funded by GDN at the outset of their grant. Often, they build longer-term collaboration with the teams and/or GDN.

We think of GDN as an integral part of the mentoring arrangement, and of independent advisors as an essential part of GDN’s approach to program management.

Where does GDN’s approach to mentoring come from?

GDN borrowed the practice from academia, where mentoring (or one-on-one supervision) is an essential strategy for training students, particularly in the case of research degrees. Our mission towards research capacity building echoes this ambition, with the important exception that our programs focus on trained researchers and established organisations implementing projects, not students. We adapted mentoring for our needs, which are to support projects and the teams that work on their design, implementation and evaluation, in addition to the personal or professional development of individuals.

What do we look for in a mentor, and how do we select them?

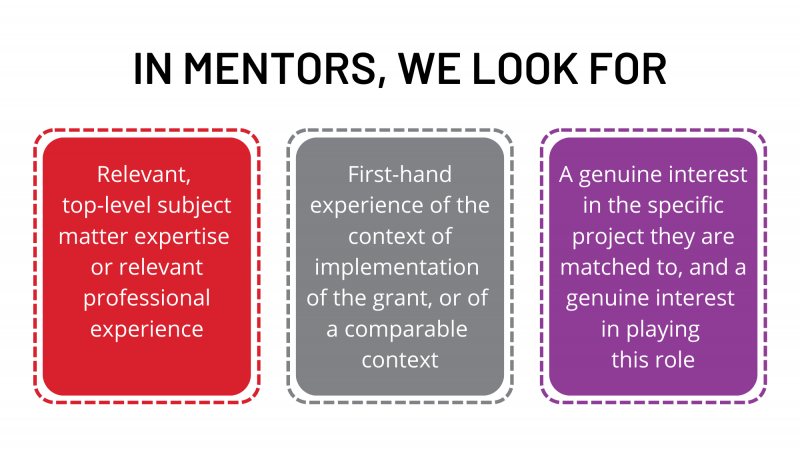

In sum, we look for capacity and commitment to build a constructive personal relationship with the teams, backed by a healthy dose of self-interest in the project itself and its success.

We probe the qualities mentioned above by articulating our expectations from the first contact with potential mentors. The first contact is followed by an ‘interview’ process to determine if the candidate is a suitable match for the program or not. This is primarily a responsibility of GDN program managers.

Mentors are typically found through careful online bibliographic and biographical searches, but they can also emerge from the Scientific Committees set up for a specific program. We also consult grantees for input and ideas on identifying potential mentors before beginning our online searches, to ensure the best match possible while allowing grantees to do a self-assessment of their needs and aspirations.

What do mentors do, in practice?

We ask mentors to share responsibility with GDN and with the grantee for the quality of the process of implementation of the project. This is done by reviewing, discussing and assessing the range of possible actions grantees contemplate, and corroborating their choices from design to implementation to dissemination. Mentors play this role in direct communication with the grantees, and they regularly share with GDN their overall assessment of the grants’ progress (including suggestions for additional support, if needed) through reports that are assessed by GDN program managers.

Grantees themselves, in turn, take full responsibility for the quality of outputs (a paper, or a change in their institution, or the impact of a development project, for example).

Mentors provide at a minimum three written reports, at the beginning, mid-point and end of the project. Typically, we expect mentors and teams to take upon themselves to develop a calendar of check-in meetings and select a modality of interaction - agreeing on a communications plan for the duration of the grant. The objective is to create a shared space and co-leadership in the arrangement, supporting open communication and critical discussion.

Do we evaluate mentoring?

The mentoring arrangement is evaluated from the perspective of all three actors involved:

- Grantees comment on the mentoring arrangement in all progress reports (questions about the nature, frequency and benefits of mentoring, including reasoned disagreements, standard questions in grant reporting templates),

- Advisors are asked to provide a final assessment of their experience at the end of the project

- GDN program managers discuss all steps of mentoring with their unit heads on a routine basis

What is the future of mentoring at GDN?

Considering the key role enhanced program management and evaluation practices play in the circulation of information that is by definition rich and ‘evaluative’, we are reflecting on the potential of advancing mentoring as a pathway to enhance ‘program evaluation’ practices - minimizing the current overreliance on external and ex-post evaluations. The field of strengthening research capacity has for long, lacked a reference evaluation framework and practices, making evidence-based approaches to capacity building design and the formulation of evidence-based value propositions for the sector extremely challenging. Tapping into the knowledge of mentors could offer a lateral approach to addressing this gap. Future steps might include developing a training curriculum for mentors, and launching a roster and a community of practice.

If you are interested in knowing more, contact Francesco Obino.